Ronald Janssen

Probably one of the most popular slogans of the entire European Semester is the catchphrase that wages should be aligned with productivity. The reason for its popularity is that this phrase can be used with a lot of flexibility.

On the one hand, the Commission can make use of it to discipline wages and undermine national systems of wage formation, a trend which has become all too common in many member states these last years. On the other hand, when being accused of biased against wages, the Commission can refute this accusation and claim that its approach is balanced and fair since it is pushing for stronger wage increases in those countries where wages have lagged behind productivity developments.

The latter, unfortunately, is far removed from what the Commission is actually doing in practice. As I will argue in this text (and a full study is available here ), there is a large and growing majority of member states that is suffering from wages staying behind productivity and this dismal development is not at all being reflected in the Commission’s country specific recommendations. On the contrary, the Commission’s approach is instead based on the assumption that the opposite is the case and that wages have seriously outpaced productivity developments and need to be brought back down so as to restore equilibrium.

The Facts: Workers Are Not Living Beyond Their Means

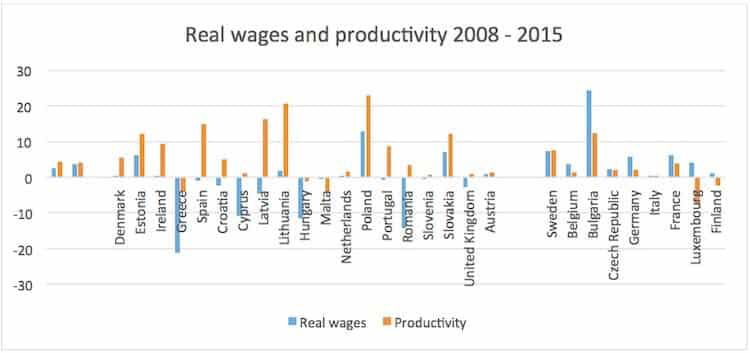

The first graph below shows the cumulated increase in real wages and productivity since the start of the financial crisis in 2008 and ending with the Commission’s forecasts for 2015. Over this 7 year period, and with a few exceptions such as Spain and Poland, productivity developments have been compressed because of the impact of the double dip recession and the severe downturn in aggregate demand. Real wages, however, also reacted to the crisis and to such an extent that their increase ended being lower than productivity in an overwhelming majority of member states, 19 to be precise.

Moreover, these gaps between wage and productivity developments are often substantial. They go as high as 10-15 percentage points in Poland, Romania, Portugal, Greece, Spain, Hungary, Slovakia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ireland. For Europe as a whole, the average numbers are that productivity over this seven year period increased by 4.3% whereas the evolution in real wages remained limited to just 2.4%.

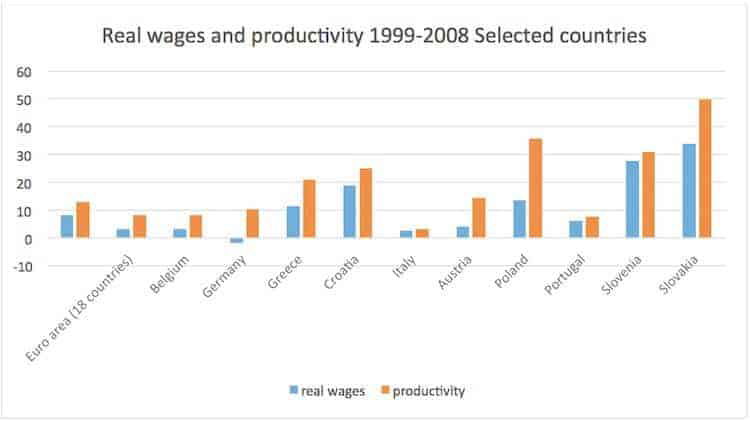

This is not a new phenomenon. In the decade before the financial crisis (see next graph below), from 1999 to 2008, real wage dynamics also failed to keep up with productivity. Even though average productivity in Europe went up by 13% from 1999 to 2008, average real wage increases were limited to 8%. These average numbers were especially driven by two big Member States, Germany and Poland. In Germany, 2008 real wages were actually 2% below their 1999 level. Smaller countries such as Austria, Belgium and Slovakia were also part of this group.

While this trend of real wages falling behind productivity has been with us for many years, this phenomenon is now spreading across more and more Member States. The number of member states experiencing this trend has almost doubled from 10 in the 1999-2008 period to 19 in the 2008-2015 period. And if one pieces the numbers together by looking at the evolution over the entire past decade and a half, then some really spectacular numbers come out. In Poland for example, productivity has outpaced real wage developments from 1999 to 2015 by an astonishing 40 percentage points (pp). In Greece, the gap is 27pp. In Spain, we are talking about a 15pp gap. In Germany, despite more favourable developments in real wages over the recent years, the gap is still 9 pp.

Wage Depression: The European Semester Is Turning A Blind Eye

Given these numbers and with more and more Member States getting contaminated by this trend, one would expect the Commission to express concern and to formulate corresponding policy proposals. However, in the thousands of pages of policy analysis that make up the European Semester, from the Annual Growth Survey over the in-depth country studies up to the country specific recommendations, not a single reference to this problem of wage dumping can be found.

Even worse, the Commission does not simply turn a blind eye to the wage race to the bottom. It is actively promoting a further weakening of wage dynamics.

An analysis of the country specific recommendations the Commission issued last year shows that all recommendations concerning wages are negative and aimed at keeping wages down. In Belgium, Luxembourg and Italy, indexation systems linking wages to inflation are under fire. In France and Slovenia, the Commission considers the level of minimum wages as too high, without at the same time providing convincing evidence to back this up. Concerning Spain, the Commission welcomes the reforms that were introduced by the conservative government at the beginning of 2012 and which give individual employers the right to cancel existing collective agreements and unilaterally impose lower wages. Meanwhile, Denmark and Finland are being called upon to conclude moderate wage agreements in the future.

In addition to recommending reforms, the Commission, as part of the Troika, is directly imposing policy action on wage bargaining systems in Member States that are in financial distress, with cuts and freezes in minimum wages and in both public as well as private sector wages as a consequence.

Summing up, even though wages have already lost out, the Commission has embarked on a ‘mission to destroy’ robust systems of wage formation to push wages down even further. It is as if the protection that these systems offer to wages and the bargaining position of workers and trade unions has been declared as public enemy number one.

The Consequences: Hitting The Wall Of Debt Deflation

If the Commission ignores or even promotes the wage race to the bottom, this is because it is obsessed with the notion of wage competitiveness. Having declared the strategy of fiscal austerity – with its dire consequences on domestic demand – as unavoidable and necessary, all hopes have to be pinned on demand coming from the outside. And to trigger export-led growth, wages need to give in, especially in a monetary union where the instrument of currency devaluation is missing. This approach however overlooks two basic things.

First, Europe is anything but a small open economy: With the share of exports going to the rest of the world limited to just 17% of European GDP, it does not make sense to push wages down across Europe. Such a strategy will simply result in depressing other Member States’ export markets while the share of exports going out of Europe is simply too small to make up the difference. The basic fact is that Europe cannot steal jobs from itself.

Second, there is the danger of “debt deflation”, with too low inflation rates automatically and continuously pushing up the real burden of debt, thereby crowding out aggregate demand by forcing debtors to spend a higher share of their income on debt service payments. Policy makers would do well to remind themselves that in cases in which total debt reaches 200% or 300% of GDP, the debt ratio is being pushed up each and every year by 2 or 3 percentage points every time inflation falls by 1%. In this way, too low inflation pushes debt ratios upwards and the economy downwards into a situation of prolonged weak demand and persistent depression.

After The Elections

Now that the European elections are behind us, the interesting question is whether Europe will continue on its dead end road of wage dumping or whether it will change course. For the sake of Europe and its economy, one can express the hope that the European “Masters of Austerity and Wage Deregulation” will come to their senses and rediscover wages as an engine for demand and growth as well as a powerful safeguard against financial instability and the danger of debt deflation. The first test will come next week, on the 2nd June, when the Commission is expected to launch the new 2014 round of country specific recommendations.

Ronald Janssen is senior economic adviser to the Trade Union Advisory Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. He was formerly chief economist at the European Trade Union Confederation.