‘Inequality’ is never the official cause of a death. But, writes Jayati Ghosh, that doesn’t mean it’s not.

The pandemic brought home to us a hard truth. Unequal access to incomes and opportunities does more than create unjust, unhealthy and unhappy societies—it kills people.

Over the past two years, people have died when they contracted an infectious disease because they did not get vaccines in time, even though those vaccines could have been more widely produced and distributed if the technology had been shared. They have died because they did not get essential hospital care or oxygen when they needed it, because of shortages in underfunded public health systems. They have died because other illnesses and diseases could not be treated in time, as public health facilities were overburdened and they could not afford private care.

They have died because of despair and desperation at the loss of livelihood. They have died of hunger because they could not afford to buy food. And they have died because their governments could not or would not provide the social protection needed to survive the crisis.

While they died, the richest people in the world became richer than ever—and some of the largest companies made unprecedented profits.

Every four seconds

A recent paper from Oxfam shows the extent to which inequality has grown during this period of global calamity. The wealth of the ten richest men has doubled, while 99 per cent of humanity is poorer. And this increasing inequality has been associated with at least one death every four seconds, in some of the ways I have just described.

The hundreds of millions of people who have suffered disproportionately during this pandemic were already likely to be more disadvantaged. They were more likely to live in low- and middle-income countries, to be women or girls, to belong to groups experiencing social discrimination, to be informal workers. More likely, therefore, to be unable to influence policy.

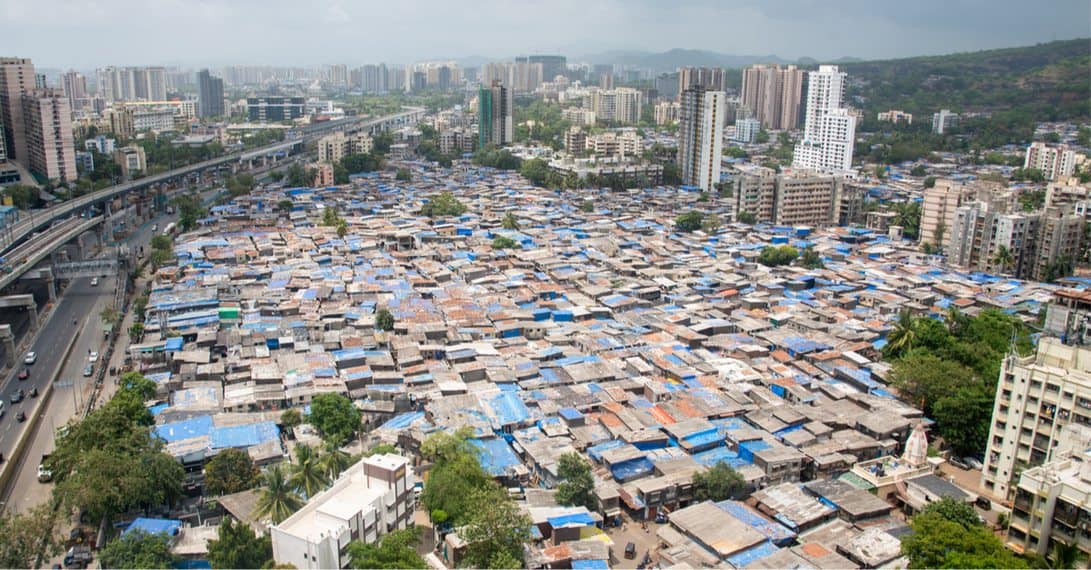

In my own country, India, the number of dollar billionaires increased from 102 in 2020 to 142 in 2021. This even as much of the Indian population was devastated by the pandemic and associated livelihood collapses and the wealth share of the bottom half of the population fell to only 6 per cent.

Yet, even in this period, state policies have operated to increase further the power of the wealthy over everyone else—by trying to prop up private ‘investor confidence’ through more tax concessions, more enabling of private monopolies, further relaxation of rules for protecting the environment and yet more labour-market deregulation destroying workers’ rights.

Killing the planet

Now it appears that inequality is not just killing those with less political voice—it is also killing the planet. Oxfam estimates that 20 of the richest billionaires in the world are on average responsible for the emission of 8,000 times as much carbon dioxide as one billion of the poorest people.

This may come as no surprise to those who have been watching the super-rich take extra-terrestrial joyrides into space, at a cost of $55 million per ticket, in just one of the many ways in which their conspicuous consumption affects the ecosystem. As the rich in different countries have got even richer (and more politically powerful) they have also become more blatant and uncaring about their environmental impact—or happy to render lip-service rather than pursue real change in their patterns of investing and living.

This makes the strategy of privileging profits over people not just unjust but monumentally stupid and potentially catastrophic. Economies will not ‘grow’ and markets will not deliver ‘prosperity’ to anyone, no matter how powerful, on a dead planet.

Political choice

It is both essential and eminently possible to change course. This massive and deadly increase in inequality is not pandemic-driven but policy-driven. Another powerful description of recent trends, the World Inequality Report 2022, makes clear that inequality is a political choice.

That choice is made at both national and international levels. Globally, inequalities are as extreme as they were at the peak of western imperialism in the early 20th century. According to the latter report, the global income share of the poorest half of the world’s population is only around half what it was in 1820, before the great colonial divergence. Yet within-country inequalities have grown even faster, with income and wealth inequalities exploding at the very top of the distribution and private wealth almost wiping out publicly held assets in many countries.

This obviously calls for systemic solutions: a greater role for public ownership and public provision in meeting essential basic needs and furnishing social services, an end to the privatisation and commercialisation of knowledge through the regime of intellectual-property rights and much more extensive and effective regulation of private activity so as to serve common social goals. This requires reversal of the disastrous privatisations of past decades—of finance, knowledge, public services and utilities, of the natural commons.

There are also to hand fiscal policies, such as taxation of the wealthy and of multinational corporations, which only require sufficient political will. Undoing the structural inequalities of gender, race, ethnicity, caste and so on, which feed into the economic disparities, will be more difficult but is also essential, and strategies are again available which have been proposed in different contexts.

So inequality is deadly—but the solutions are within our grasp. It can still be tackled, with greater collective imagination and public mobilisation. Without it, we are all dead—and perhaps well before Keynes’ ‘long run’.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Jayati Ghosh, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, is a member of the Club of Rome’s Transformational Economics Commission and co-chair of the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation.