Why do the Maastricht criteria compare budget deficits and public debt with GDP rather than budget revenues? That’s a good question.

The European fiscal rules were conceived about 40 years ago, when the main concern was curbing inflation, and deserve some adjustment, particularly after the Great Recession, since nowadays the main issue is sluggish growth. The Maastricht criteria respectively constrained budget deficits to 3 per cent and public debt to 60 per cent of gross domestic product. The rules should take into account the role of fiscal multipliers and spillovers across the member states, but also measurement issues which plague the debt-to-GDP ratio focused on by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

The first issue has been addressed in the ‘Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the economic policy of the Euro Area’ released in December 2019, which apparently revives the Keynesian view of the capacity of fiscal stimulus to decrease the debt-to-GDP ratio under many conditions. Particularly, a technical annex reports the multipliers for the main public budget items, estimated for a downturn of GDP and when monetary policy is accommodating.

Fiscal stimulus

These show how even current government expenditure and targeted subsidies have a positive impact on GDP larger than their initial amount, at least in the short run. By contrast, the multipliers of tax are much less than one.

This implies that, when GDP slows, a fiscal stimulus financed by current revenues may accelerate income and reduce the debt-to GDP-ratio. If this is the case, the European fiscal rules must take into account the negative feedback of budget consolidation on GDP and also on the debt-to-GDP ratio, if the latter exceeds approximately the reciprocal of the fiscal multiplier.

What is more, fulfilling the SGP criteria is counterproductive for debt consolidation if the fiscal multipliers or the debt-to-GDP ratio are large enough. It follows that the limits to debt and deficit cannot be set once and for all, independently of fiscal multipliers—although the commission does not mention this consequence of its recommendation.

Questionable criteria

Another issue, seldom raised by scholars, makes the SGP criteria questionable if the sustainability of debt is the main concern. The public debt may be reimbursed and serviced by withdrawing the required resources from the budget, rather than from GDP. And only public assets could be seized in case of state insolvency, not the private incomes included in GDP. It thus makes more sense to focus on the ratio between debt and public revenues than the conventional ratio to GDP.

The same point holds for evaluating the size of the budget deficit. For instance in 2019, when public revenues were about 46 per cent of GDP in the eurozone, the limits set in the SGP should be restated as a debt not exceeding 129.5 per cent of revenues and the deficit about 6.5 per cent of the same item.

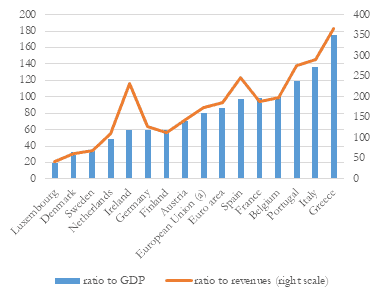

Ratios to revenues do not provide a ranking of member states so different from the traditional measure, as indicated in Graph 1. Only Ireland would slip four positions, possibly because Irish taxation is very generous—particularly for corporations. Yet changing the denominator of the SGP ratios has many intriguing consequences.

Vicious circle

First, public revenues are certified accounting items, while GDP is the results of statistical estimates which are subject to errors and even large retrospective revisions. Thus, a fiscal policy deemed appropriate according to GDP figures published at the time of implementation could turn out to be wrong—if not counterproductive—when GDP data are revised after 3-4 years. During the sovereign-debt crisis this issued in a vicious circle between downward-biased estimates of potential output (derived from misestimates of current GDP) and larger than necessary fiscal adjustments. Such an eventuality would be almost impossible using public revenues as the denominator.

Graph 1: public debt in the European Union (2019)

Secondly, the measurement of GDP depends on international standards, which can change over time. At the moment, it includes odd items—such as incomes from some irregular activity (firms evading tax, rules and duties) or even criminal actions (prostitution, drug smuggling, trading stolen goods). Eurostat (under)estimated that criminal activities alone account for about 0.5 per cent of GDP in Europe and irregular incomes currently reach about 20 per cent.

It follows that government could be tempted to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio by allowing the irregular and criminal economy to develop: relaxing laws on drugs, launching a general amnesty or cutting funds for police and justice could all increase GDP. Of course, such policies cannot be recommended and setting deficit and debt targets as ratios of public revenues would make them futile as well. On the other hand, fighting tax evasion, and so raising public revenues, would then help to meet European fiscal targets.

Policy recommendations

Setting the fiscal thresholds in terms of revenues also makes the impact of tax changes on the ratios easy to evaluate. For instance, a tax cut increases the stock of debt and decreases the revenues exactly by the same amount, every time and everywhere, so that it unambiguously raises the debt-to-revenues ratio. The same holds if expenditure cuts compensate the tax cut. Yet the same fiscal measure can have different impacts on debt-to-GDP ratios depending on the fiscal multiplier, which can change across countries, over time and for specific items of the budget. So setting fiscal targets on the revenues ratios also makes fiscal-policy recommendations more clear-cut.

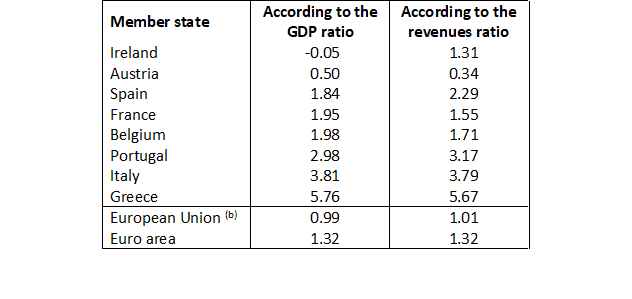

The last two columns of Table 1 report the budget surplus (as percentage of GDP) required in high-debt countries in the next year to reduce by 1/20 the distance between the current debt ratio and that required by the SGP and the revenue criterion respectively. The correction for the business cycle and the other adjustments foreseen by the SGP (such as population ageing) are disregarded for the sake of simplicity.

As expected, the fiscal effort prescribed by the two criteria is not very dissimilar (it is also the same in the eurozone and the European Union as a whole) but it falls slightly below the SGP requirements in five countries out of eight. This markdown may help growth and the political sustainability of debt-reduction plans—in turn a crucial issue for the expectations of financial markets. Notably, a surplus is required by the ratio to revenues in Ireland, because of its exceptionally low revenues-to-GDP ratio, although the Irish debt-to-GDP ratio is below 60 per cent.

Table 1: balance required to reduce the public debt at the pace prescribed by the SGP (2019) (a)

In sum, setting fiscal targets based on public revenues instead of GDP is not a gimmick to weaken the European fiscal rules, but brings many advantages, in terms of quality, transparency and consistency of policy over time. Hopefully, it could be a step ‘to enhance the effectiveness of the framework in delivering on key objectives’ of the SGP, as sought in the public consultation recently launched by the commission.

Enrico D’Elia is an economist who has worked, among others, for Eurostat as well as the Ministry of Finance, the Statistical Office and the Institute for Economic Analysis of Italy. He has written about a hundred papers on macroeconomics, behaviour of firms and households, inflation and economic forecasting. The views expressed here are entirely his own.