Standard employment is not simply being replaced by non-standard work. But work is becoming more diverse and policy must accordingly become more tailored.

The last decade has seen much public and policy debate on the future of work. Standard employment—permanent, full-time and subject to labour law—is still dominant in Europe and non-standard work, with the exception of part-time work, has been growing only to a rather limited extent. But it is more and more acknowledged that something is happening on the European labour market which is not transparent from the data, that this is of increasing importance and that it is influencing the quality of work and employment.

To probe further, in 2013-14 the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) conducted a mapping of ‘new forms of employment’ across the European Union and Norway. It identified nine trends, emerging or of growing importance since about 2000, on the European labour market. These related to formal relationships between employers and employees different from the established one-to-one employment relationship, uncommon work patters or work organisation (notably related to time and place of work), networking and co-operation among the self-employed, or some combination of these.

The employment form most often identified as new or increasingly important by then was ICT-based mobile work. Here an employee or a self-employed person works from various locations outside the traditional workplace—less place-bound than traditional teleworking and indeed working ‘anytime, anywhere’.

While this trend can be attributed to digitalisation as well as societal change, the second biggest trend—casual work—is rather driven by economic requirements of employers. In this employment form, the employer is not obliged to provide the worker with regular work but can call them in on demand, resulting in an unstable and discontinuous work situation for the employee.

Rising platforms

As the European labour market is in flux, in 2020 Eurofound repeated its mapping exercise, this time to explore how prevalent the nine previously new forms of employment had become. ICT-based mobile work, identified by about 60 per cent of the analysed countries as new in 2013-14, now exists in all countries. Casual work, previously found to be new in about 44 per cent of the analysed states, is now prevalent in about 86 per cent.

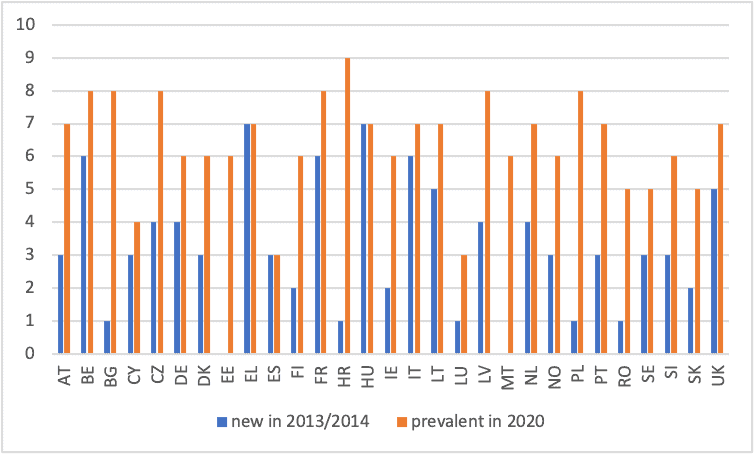

Some caution is called for when comparing the two mapping exercises due to the different underlying questions (whether an employment form was new since about 2000 versus whether it existed in the country in 2020) and slight differences in coverage (Estonia and Malta did not take part in the earlier survey). But the substantial furtherance of all nine trends justifies the claim that new forms of employment are of increasing importance in Europe. Particularly striking is the rise in platform work, which was new in about 40 per cent of the countries in 2013-14 but exists now in over 95 per cent of them (Figure 1).

Figure 1: New forms of employment in Europe, identified as ‘new’ in 2013-14 versus prevalent in 2020 (number of countries)

The new employment forms are not only becoming more prevalent across Europe. They also contribute to greater diversity on the labour market within countries.

While in 2013-14 on average three new employment forms had been identified in the analysed states, in 2020 this was true of six on average. In 2013-14, less than 20 per cent of the analysed countries identified six or more employment forms as new; in 2020 however, almost 80 per cent found six or more to be prevalent (Figure 2).

Figure 2: New forms of employment in Europe, identified as ‘new’ in 2013-14 versus prevalent in 2020 (number of employment forms)

While discussions on the future of work and new forms of employment continue, the elephant in the room is the lack of (harmonised) concepts and definitions, which would be an important precondition for establishing regulatory frameworks and generating policy intelligence such as statistical data. Better understanding these not-so-new-anymore trends is probably even more important today than it was a while ago. They are not only part of the more structural ‘twin transition’ to the digital age and a carbon-neutral economy, but also a factor to be considered in the era of Covid-19.

Digitally-enabled new forms of employment could play an important role in the recovery, as might those found to be related to more resilient business models (for example, worker co-operatives) or contributing to a win-win situation for employers and employees alike, including in economically difficult times (such as employee-sharing). At the same time, some of the new employment forms (casual work or some types of platform work) identified as less advantageous for workers might surge due to lack of alternatives on the labour market in the crisis situation, rendering already precarious workers even more vulnerable.

Nuanced approach

Policy-makers should focus on balancing flexibility with the retention of employment standards and workers’ protection. This requires a nuanced approach: tailor-made interventions should tackle the specific opportunities and challenges inherent in individual employment forms, rather than applying a ‘one-size-fits-all’ stance across the diversity of new forms of employment.

In casual work, voucher-based work, platform work and collaborative employment, employment status should be clarified and sustainable career trajectories ensured, to avoid labour-market segmentation and to support collective voice. In the digitally-enabled new employment forms, the focus could be on monitoring and control, algorithmic management and data ownership, protection and use.

Ensuring adequate working time would be key in those new forms of employment where working hours tend to be too long or too short or characterised by unpredictability. Workers in employment forms subject to less integration in organisational structures could meanwhile be supported in skills development to enhance their employability. Finally, transversal and entrepreneurial skills could be improved and good-quality self-employment fostered in tnew forms of employment in Europe characterised by high self-organisation.

This is part of a series on the Transformation of Work supported by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

Irene Mandl is from Austria where she worked in policy-oriented socio-economic research in the field of employment/labour markets as well as entrepreneurship and industry analysis before joining Eurofound as research manager.