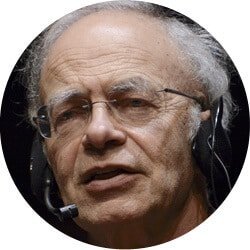

Peter Singer

From 1949, when Mao Zedong’s communists triumphed in China’s civil war, until the collapse of the Berlin Wall 40 years later, Karl Marx’s historical significance was unsurpassed. Nearly four of every ten people on earth lived under governments that claimed to be Marxist, and in many other countries Marxism was the dominant ideology of the left, while the policies of the right were often based on how to counter Marxism.

Once communism collapsed in the Soviet Union and its satellites, however, Marx’s influence plummeted. On the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth on May 5, 1818, it isn’t far-fetched to suggest that his predictions have been falsified, his theories discredited, and his ideas rendered obsolete. So why should we care about his legacy in the twenty-first century?

Marx’s reputation was severely damaged by the atrocities committed by regimes that called themselves Marxist, although there is no evidence that Marx himself would have supported such crimes. But communism collapsed largely because, as practiced in the Soviet bloc and in China under Mao, it failed to provide people with a standard of living that could compete with that of most people in the capitalist economies.

These failures do not reflect flaws in Marx’s depiction of communism, because Marx never depicted it: he showed not the slightest interest in the details of how a communist society would function. Instead, the failures of communism point to a deeper flaw: Marx’s false view of human nature.

There is, Marx thought, no such thing as an inherent or biological human nature. The human essence is, he wrote in his Theses on Feuerbach, “the ensemble of the social relations.” It follows then, that if you change the social relations – for example, by changing the economic basis of society and abolishing the relationship between capitalist and worker – people in the new society will be very different from the way they were under capitalism.

Marx did not arrive at this conviction through detailed studies of human nature under different economic systems. It was, rather, an application of Hegel’s view of history. According to Hegel, the goal of history is the liberation of the human spirit, which will occur when we all understand that we are part of a universal human mind. Marx transformed this “idealist” account into a “materialist” one, in which the driving force of history is the satisfaction of our material needs, and liberation is achieved by class struggle. The working class will be the means to universal liberation because it is the negation of private property, and hence will usher in collective ownership of the means of production.

Once workers owned the means of production collectively, Marx thought, the “springs of cooperative wealth” would flow more abundantly than those of private wealth – so abundantly, in fact, that distribution would cease to be a problem. That is why he saw no need to go into detail about how income or goods would be distributed. In fact, when Marx read a proposed platform for a merger of two German socialist parties, he described phrases like “fair distribution” and “equal right” as “obsolete verbal rubbish.” They belonged, he thought, to an era of scarcity that the revolution would bring to an end.

Human nature

The Soviet Union proved that abolishing private ownership of the means of production does not change human nature. Most humans, instead of devoting themselves to the common good, continue to seek power, privilege, and luxury for themselves and those close to them. Ironically, the clearest demonstration that the springs of private wealth flow more abundantly than those of collective wealth can be seen in the history of the one major country that still proclaims its adherence to Marxism.

Under Mao, most Chinese lived in poverty. China’s economy started to grow rapidly only after 1978, when Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping (who had proclaimed that, “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice”) allowed private enterprises to be established. Deng’s reforms eventually lifted 800 million people out of extreme poverty, but also created a society with greater income inequality than any European country (and much greater than the United States). Although China still proclaims that it is building “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” it is not easy to see what is socialist, let alone Marxist, about its economy.

If China is no longer significantly influenced by Marx’s thought, we can conclude that in politics, as in economics, he is indeed irrelevant. Yet his intellectual influence remains. His materialist theory of history has, in an attenuated form, become part of our understanding of the forces that determine the direction of human society. We do not have to believe that, as Marx once incautiously put it, the hand-mill gives us a society with feudal lords, and the steam-mill a society with industrial capitalists. In other writings, Marx suggested a more complex view, in which there is interaction among all aspects of society.

The most important takeaway from Marx’s view of history is negative: the evolution of ideas, religions, and political institutions is not independent of the tools we use to satisfy our needs, nor of the economic structures we organize around those tools, and the financial interests they create. If this seems too obvious to need stating, it is because we have internalized this view. In that sense, we are all Marxists now.

Republication forbidden. Copyright: Project Syndicate 2018 Is Marx Still Relevant?

Peter Singer is Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, Laureate Professor in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne, and founder of the non-profit organization The Life You Can Save.