Most discussion of inequality in Europe is confined to individual member states. Aggregating incomes across the EU, however, presents a sobering picture.

How unequal is the distribution of income within the European Union? The question sounds simple but it hides a plethora of complex issues.

What income is assessed: market (before taxes and transfer payments) or disposable? Whose incomes are we comparing: people, regions, countries or classes? How do we measure inequality: absolute differences or relative extent? What indicator do we choose: the Gini coefficient or income shares and their relationships, such as the ratio of the top quintile to the bottom (S80/S20)? What database do we use: national accounts (deriving gross domestic product) or household surveys (giving disposable income)?

This article focuses on the distribution of disposable income among people based on household surveys—the EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions—using different indicators.

Substantial variation

To assess the distribution of income within the EU proper one has to take into account the distribution within and among member states. Most statistics, research and political conflict deal with inequality within countries.

This varies substantially across member states. The most egalitarian are some central-European nations (the Czech Republic, Slovenia) and the Scandinavian countries. The states with the most unequal distributions can be found in the south of the EU. In 2017, the national S80/S20 ratio ranged from 8.2 for Bulgaria to 3.4 in Slovenia.

At the same time, there are huge disparities among the average incomes of different member states. For example, gross domestic product per capita in Germany is over five times that of Bulgaria. Income differences among countries are reduced, however, if one expresses them in terms of purchasing-power standards (PPS)—because the price level tends to be lower in poorer countries the purchasing power of a given amount of money is correspondingly higher.

To get to Europe-wide inequality (measured by the S80/S20 indicator), one must order all residents of the EU (about 500 million before Brexit) according to their income, take the bottom and the top 100 million (each a quintile) and compare their respective total incomes. A good approximation of that value can be achieved by using national quintiles as the author has done over the last ten years.

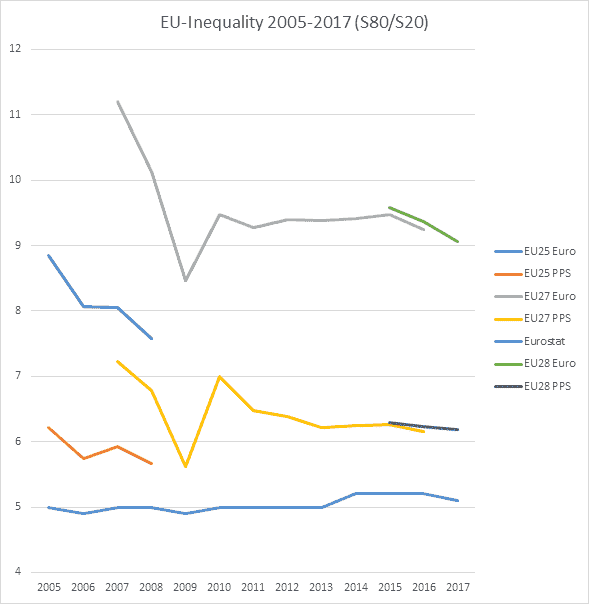

For the year with the latest available data (from 2017), this calculation delivers S80/S20 values of about six in PPS and nine (at exchange rates). Figure 1 shows the trend of Europe-wide inequality since 2005.

Figure 1: Europe-wide inequality 2005-17

The more recent eastern enlargements increased Europe-wide inequality by adding millions of people a lot poorer to the total population. Rapid growth in the poor countries has however reduced the inequality, albeit at a snail’s pace since 2011. (Note that the lowest line in Figure 1, which shows the official value given by Eurostat, is wrong on both level and trend—due to an incorrect construction of the European value as the average of national values, neglecting the income disparities among countries.)

Does Europe-wide inequality matter, given most people, studies and politics are concerned with inequality within nations (if at all)? Europe has become a kind of country, at least economy-wise due to the deep integration of its markets for goods, services, labour and capital. Capital has moved investment and production from high-wage to low-wage locations, such as from Germany to eastern Europe. With free movement of labour, workers have moved from low-income to high-income countries, for instance from Poland to the UK. (Partly) as a result, Britain has chosen to leave the EU—European income disparities really matter!

Palma ratio

To understand inequality better, one can apply a different approach following the work of the Chilean economist José Gabriel Palma. He highlighted what has become known as the ‘Palma ratio’, between the income of the top decile and that of the bottom four. Palma had discovered that the variation of inequality among countries is almost exclusively caused by differences in the Palma ratio. The share of the upper-middle half of the population—the five deciles below the top one—varies much less and is virtually the same (around 50 per cent) for all countries.

The Palma ratio for EU member states varies between 0.9 (low inequality) and 1.6 (high inequality) and is strongly correlated with other measures, such as the S80/S20 ratio or the Gini. The share of the upper-middle strata (the 50 per cent) hardly varies and thus confirms the findings by Palma. The national distribution of income depends largely on how much the top decile can take from the bottom 40 per cent. In international comparison, however, all EU member states are less unequal than most countries in the world, which often have Palma ratios higher than two.

A Europe-wide Palma ratio can be derived using the same method as in estimating the S80/S20 ratio. The top decile of the EU population (about 50 million) is constructed (by adding the respective national quintiles) and its income compared with that of the bottom 40 percent (about 200 million). The resulting Palma ratio is 1.33 at PPS and 1.69 at exchange rates. With these values, the EU as a whole is more unequal than any single member state when measured at exchange rates (Figure 2).

Figure 2: the Palma ratios of the EU and its member states (2017)

The EU as a whole, however, is different from the member states in one respect: the share of the upper-middle half (about 250 million people) is higher than in most national economies. It is approximately 60 per cent—slightly less if measured at PPS—or almost ten percentage points higher than the average national value.

Palma interprets his finding as indicating the political and economic power of the middle classes to defend their income position against competition from below and exploitation from above. In the case of the EU, the ‘middle class’ consists to a large extent of the population of the richer countries except the top and bottom quintiles (the respective European deciles being constructed out of national quintiles).

Obviously, these strata are better ‘protected’ within the European economy than their national counterparts in their respective economies. This situation is hardly surprising: although the EU is a highly integrated economic space, national economic advantages (human and physical capital and intangible assets) and policies (the welfare state) still play an enormous role.

Nonetheless, there are groups in the richer countries which are affected by competition via migration or relocation of low-skill production, leading to higher inequality within many richer member states. And many poorer member states show higher growth rates than the richer countries, also thanks to the integration in the European economy.

The overall convergence of income levels within the EU, as Figure 1 shows, remains relatively slow. Cohesion must be prioritised and accelerated by appropriate policies—at the EU level and in the member states.

See also our focus page What is inequality?

Michael Dauderstädt is a freelance consultant and writer. Until 2013, he was director of the division for economic and social policy of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.