The consensus against German fiscal rebalancing is cracking—because the export demand which allowed it long to be avoided is looking shaky.

The European Commission, consecutive US governments and countless others have spent a decade trying and failing to convince Angela Merkel’s governments to spend more at home, rebalancing the overly export-dependent German economy. Lately, their chorus has been joined by a vocal group of homegrown critics—including Germany’s business lobby.

Is this finally a sign that change is on the way? With growing trade uncertainty in the very regions which propelled German growth in the post-crisis years, ‘more of the same’ is no longer a viable approach.

Dogged adherence

The last few months have seen a shift in public discourse over German economic policy. Hitherto, it was mainly outside voices who were criticising Germany for thwarting global recovery, nagging (in some cases demanding) Berlin to boost spending. But critics on the inside have grown louder too. Influential German economists and Green politicians have urged the government to rethink its dogged adherence to balanced budgets. The most striking intervention to date came from Dieter Kempf, leader of Germany’s industrial lobby, who called for fiscal policy to abandon the constitutional ‘debt brake’ (Schuldenbremse).

Germany’s refusal to adjust is puzzling. If it did so, it could reignite slowing growth while locking in historically low interest rates.

The explanation could lie in Germans’ cultural attachment to prudence, but that does not explain why we do see large stimulus packages from time to time. It is often forgotten, for instance, that in 2009, Germany undertook a most extensive set of stimulus measures. Other explanations point to German industry safeguarding its cost-competitiveness from (inflationary) fiscal accommodation, but Kempf’s recent statement and survey evidence from Stefanie Walter and her co-authors demonstrate that industry is actually quite open to stimulus.

Hard to swallow

For policy-makers to fix something, they need to be persuaded that it’s broken—and Germans find it profoundly counter-intuitive that their export surplus is problematic. For starters, it is hard to swallow that a booming economy with record-low unemployment gets scolded by problem-children like the US or eurozone partners. So how to reconcile the harsh criticism with the German economy’s stellar performance?

The most fitting explanation looks beyond the often introverted world of German politics—at global economic trends enabling German policies. Although critics are right to point out that Germany has a domestic spending problem, it does not lead to unemployment (as it normally would), because Germany successfully relies on foreign demand. Trading partners willing to run deficits mirroring German surpluses have cushioned the fallout from domestic policy flaws.

One of the many misunderstandings about the export surplus is that criticism is directed at Germany for being ‘too competitive’ and ‘exporting too much’ (sidetracking the discussion towards real exchange rates and competitiveness), when in fact the issue is on the other side of the balance—spending too little at home. More fruitful discussions often start by calling the export surplus an import deficit (which it is, by definition), as does the economist Marcel Fratzscher.

A closer look at Germany’s domestic demand problem illuminates why the strikingly large and sustained surplus (surpassing China’s in absolute terms) is not only bad for the world economy but bad for Germany too. Suppressed wages mean that income has shifted from labour (with high propensity to consume) to capital owners, leading to rampant inequality and weak household consumption while driving up savings. In addition, low private and public investment creates an investment gap which hurts supply potential and competitiveness in an era of rapid technological transformation. This excess of savings and insufficiency of investment leads to the observed current-account (CA) surplus.

On the flipside of CA surpluses, excess savings flow into foreign assets often beyond the productive investment needs of a deficit country, fuelling asset-price bubbles, leading to eventual losses for German savers. But these are indirect and long-term costs, which rarely ignite domestic pushback.

The central political obstacle to German rebalancing in the last decade was the availability of an exit option: keep relying on external demand to escape unemployment, even in the face of weak domestic spending. It has been a path of least resistance and an alternative to an internal adjustment that is messier and politically more difficult than often acknowledged.

Skyrocketing uncertainties

So what has changed now? The exit option was opened up by more spending from China, the United States and the United Kingdom—precisely the countries where trade uncertainties have recently skyrocketed.

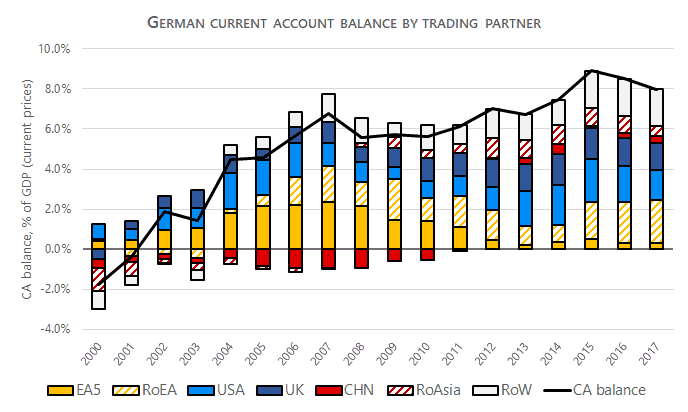

The figure below shows the German surplus, its sources decomposed by global regions. Before the crisis, the main trading partners were the five euro-area periphery countries (EA5 in the figure) which became known as the ‘PIIGS’: Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain. From 2008, there was a sharp drop in their share—a sign of rebalancing with Germany. Importantly, however, this was mainly due to an austerity-driven collapse of imports on the periphery rather than increased German demand (so it is hardly a sign of German rebalancing).

As the euro crisis hit, it was plausible to assume that the collapse of the periphery would force Germany to spend more and gradually rebalance. But it did not and the surplus kept increasing. What gradually changed was the share of China, the US and the UK.

After the financial crash, China rebalanced its economy dramatically (cutting its CA surplus from 10 per cent of GDP in 2010 to 1.6 per cent in 2017) and Germany could capitalise on this: its sizeable negative bilateral balance switched to positive. Meanwhile, partly fuelled by more accommodative fiscal and monetary policies, recovery in the US and UK outpaced that of Germany and the eurozone—it was well under way as the eurozone plunged back into recession in 2011. The two continued to run CA deficits in the period (an average of -4.2 per cent for the US, -2.5 per cent for the UK). This created even more room for German exports, and the US and UK saw their bilateral deficits with Germany swelling.

These tectonic shifts in global aggregate demand were necessary conditions for Germany to stick to its guns and refuse stimulus. In a hypothetical scenario without an upsurge in external demand, German policy-makers would have likely been much more invested in domestic stimulus. And, indeed, a similar scenario presented itself in 2008-09, when export-market collapse was more widespread—duly triggering a large stimulus package.

Trade war

Today, the trading partners who saved the day years ago do not look like a safe bet. China and the United States are locked in a bitter trade war and US tariff threats are also directed towards Germany. The UK is sinking into unprecedented instability induced by ‘Brexit’. No wonder the prospects of German exporters have suddenly turned bleak and the policy discussion is a lot more attuned to reasonable criticisms.

The grace period when foreign demand washed away the domestic costs of weak spending is likely to be edging towards the end. But for German rebalancing to happen, it may need to get a lot worse before it gets better.

Pálma Polyák is a PhD candidate at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Florence. She is working on the domestic and global politics of export reliance and current-account surpluses, focusing on the eurozone's surplus countries.