The good news is that unemployment has only risen modestly so far; the bad news is that hours worked have plummeted.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented setback to economic activity across the world, not least in Europe. Supply chains broke down, disrupting industrial production. Many activities, particularly in services, were halted by administrative restrictions. The associated losses of income—even if cushioned by government interventions of various sorts—and heightened uncertainty deflated demand and led to further output losses.

Production in the European Union fell in the first quarter of 2020 by more than 3 per cent, only to plunge in the second quarter by a further 11.4 per cent, shattering records. In particularly hard-hit countries the losses have been even more dramatic.

This fall in production could have been expected to lead to a sharp rise in unemployment. Yet while unemployment has risen it has remained modest, given the size of the shock: the latest rates, for August, are 8.1 per cent for the euro area and 7.4 per cent for the EU as a whole—only 0.6 and 0.7 percentage points respectively above their levels a year earlier.

Clearly the change in unemployment is not telling us anything like the whole story of the impact the crisis has had on labour markets. Just-released Eurostat data for the second quarter of the year allow us to flesh out the picture, at least up until the end of June.

Labour-market withdrawal

The flows between the three labour-market statuses—employed, unemployed and economically inactive—provide a good starting point. ‘Inactive’ (an unfortunate term) refers to those of working age who are not employed but who are, in contrast to the unemployed, not looking for work or not available in the short run. It covers a diverse range of groups, including students, but notably individuals, often women, providing care in the household.

While 2 per cent of those employed in the first quarter were unemployed in the second, almost twice as many (3.4 per cent) became economically inactive between April and June. In net terms—some moved in the opposite direction—1.2 million went from a job to unemployment but 2.6 million dropped out of the labour force entirely. On top of this, 1.1 million who were unemployed in the first quarter withdrew from the labour market in the second quarter—again in net terms.

Specific reasons for entering inactivity in recent months include having become unavailable for work due to having to look after children following the closure of schools and childcare and having abandoned job search because of the perceived impossibility of finding work under crisis conditions. From a macroeconomic point of view, the rise in inactivity (‘labour-market withdrawal’) is no less problematic—in some cases arguably more so—than the rise in unemployment.

Working-time adjustment

A second reason why reduced labour demand need not show up in open unemployment is that workers retain employed status but work fewer hours. This can take two main forms: temporary (complete) absence from work and a reduction in hours. In most cases the former is tantamount to unemployment in the short run (although the employment link is maintained); the latter can be considered equivalent to unemployment in proportion to the extent of working-time reduction.

The latest Eurostat figures show that temporary absences from work shot up from around 12 to 22 per cent of workers between the first and second quarters (seasonally adjusted). Temporary layoffs were by far the most important factor: affecting hardly any workers at the end of 2019, they struck almost 20 million in the second quarter.

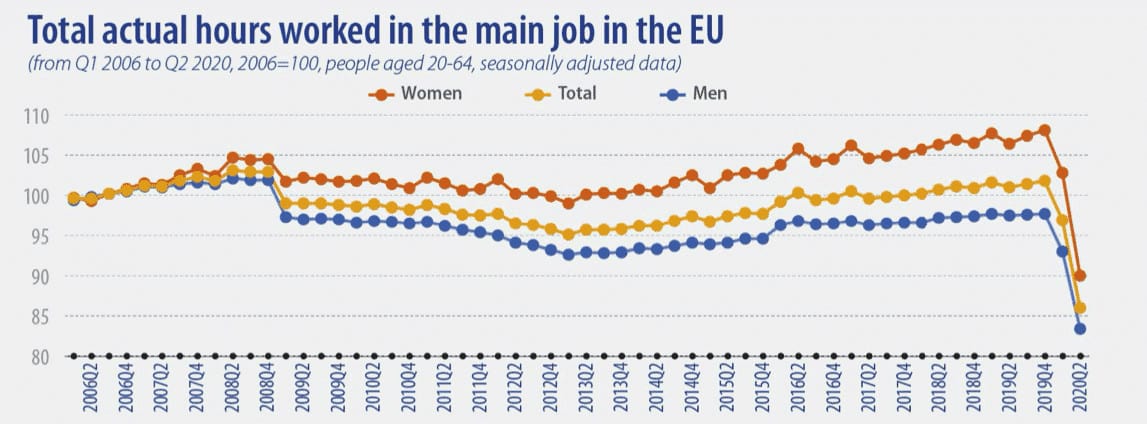

Just under 40 per cent of Greek workers were temporarily laid off in quarter two—around one third of the employed in Cyprus and more than a quarter in Spain, France, Ireland, Portugal and Italy. On top of this come agreed reductions in individual working time. Together with actual employment losses, these resulted in a massive overall fall in total hours worked—around 12 per cent in Q2 (see graph).

Bringing all these elements together provides a fuller and more realistic picture of the impact of the pandemic on EU labour markets. Eurostat estimates labour-market slack by adding to the unemployed underemployed part-time workers and those not seeking or not available for work. In the second quarter that amounted to almost 30 million people across the EU, representing 14.0 per cent of the extended labour force, up from 12.8 per cent in the first quarter. This was the highest quarter-on-quarter increase since the beginning of the time series in 2008.

Outlook

Given the size of the economic shock it is welcome news that a very substantial rise in unemployment has been avoided … so far. Government schemes, especially vis-à-vis temporary layoffs and short-time working, have helped cushion the blow. Workers and employers have negotiated—or the latter have imposed—cuts in working hours, staving off redundancies.

Equally, though, many more individuals than those forced into redundancy have, at least temporarily, withdrawn from the labour market. Temporary layoffs may yet end up in open unemployment. The figures are likely to have deteriorated further since the end of June, the period covered by the most recent Eurostat data.

Moreover, fiscal pressures are forcing governments to consider how long they can continue supporting short-time working and other similar schemes. The EU’s SURE initiative is welcome in this regard, even if it only provides loans to governments.

Most ominously of all, Covid-19 cases are now on the rise again across Europe. A renewed lapse into border controls and the shutdown of entire sectors and regional economies would place severe additional burdens on Europe’s labour markets and government finances. Both member-state governments and the EU will need to be resolute in providing timely support to avoid further job losses and resultant hardship.

Andrew Watt is general director of the European Trade Union Institute.