Staff shortages represent a risk to occupational health and an EU directive should mandate member states to address them.

Staff shortages comprise the most significant challenge facing health and social care in the European Union. Even before the pandemic, the European Federation of Public Service Unions (EPSU) was underlining its gravity, on the European and global (via Public Service International) levels.

Our calls, along with the demands of other professional organisations, are increasingly reflected in initiatives by policy-makers—including the European region of the World Health Organization, the health ministers of Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development member states and the current Belgian presidency of the Council of the EU. Health is mentioned in the EU action plan to tackle labour and skills shortages, published last week. And the EPSU has just presented its own report, seeking to address staff shortages in health and social care via dedicated directives—including one specifically on safe staffing levels.

EU competences

The EU’s competences in relation to health are important but limited to public health. During the pandemic, the regulation on serious cross-border threats to health allowed joint procurement of vaccines while requiring member states to develop national prevention, preparedness and response plans, with relevant reporting systems. The EU4Health initiative saw the establishment of the Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority and strengthened the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the European Medicines Agency.

To address staffing, however—including how countries should be prepared for future pandemics—we need to go beyond the EU’s public-health competences into social policy. In areas such as working conditions the union does have a remit and here it is crucial to recognise the role of the European social partners.

Article 153 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, for example, allows the EU to co-ordinate social law with the participation of social partners. It stipulates that ‘the Union shall support and complement the activities of the Member States in the following fields: (a) improvement in particular of the working environment to protect workers’ health and safety; (b) working conditions’.

This article served as a legal basis for the 2022 minimum-wages directive, which also promotes collective bargaining. Although staff shortages are not considered part of working conditions per se, the sub-paragraph regarding health and safety can provide a legal basis to address the issue. There is extensive EU legislation on occupational health and safety (OSH), beginning with the framework directive in 1989, followed by 23 individual directives.

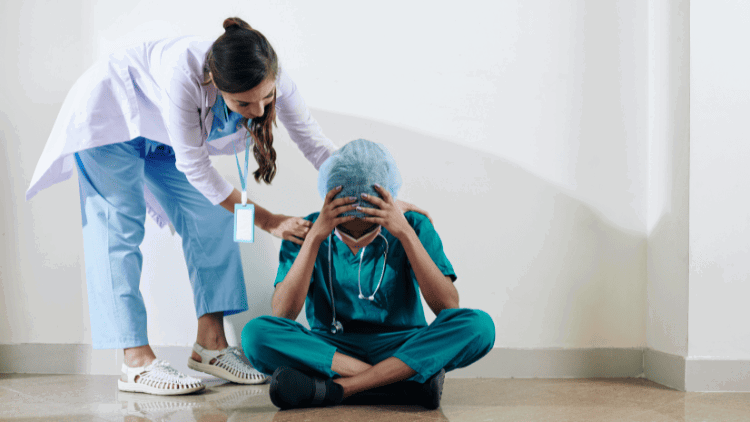

The EPSU, with other trade unions, is calling for directives on psychosocial risks (PSR) and musculo-skeletal disorders (MSD). Along with the European Trade Union Institute, it has demonstrated how these are closely connected, with stress and MSD the main causes of work-related illness among healthcare workers. With both fuelled by staff shortages, the two proposed directives would by contrast help retain healthcare workers, who report the highest stress among all occupations, according to a 2023 Eurofound report on the job quality of essential workers.

New directive

We should also open a debate on whether OSH legislation could be extended to address staffing levels directly. If in healthcare we see these not solely as a workplace planning matter but also as a potential occupational risk, then employers should take steps to protect workers from unsafe staffing—just as they would with any other such risk.

The framework directive (89/391/EEC) put the responsibility on the employer to ensure the safety and health of workers in every aspect related to their work and to ‘take the measures necessary for the safety and health protection of workers, including prevention of occupational risks and provision of information and training, as well as provision of the necessary organisation and means’. Recognising understaffing as a potential risk would thus provide an opportunity to develop a new individual directive with specific measures to protect workers in health and social care. Previously, a sectoral agreement between the EPSU and HOSPEEM (the employers’ side) on prevention of sharp injuries in hospitals and healthcare was transposed into a 2010 directive (2010/32/EU).

Action plans

Given the specificities of different health systems across the EU, a directive to address staff shortages could adopt the approach of the minimum-wages directive, when it comes to action by member states. Article 4 of that directive requires member states to work with social partners to develop action plans to achieve 80 per cent collective-bargaining coverage.

Similarly, member states could be obliged in a legally binding way to produce action plans to reduce staff shortages. They should be required to define safe staffing levels with the social partners. This approach could be adapted to different work-related settings and national circumstances, recognising the variation in recommended staffing levels across the EU.

In the absence of such a directive (or other form of EU legislation), Europe will then need an overall action plan to address staff shortages. Good examples here are the European Commission’s European Care Strategy and the council recommendation on access to affordable, high-quality, long-term care. It could be said that the care strategy implements principle 18 of the European Pillar of Social Rights, though implementation of principle 16 (‘Everyone has the right to timely access to affordable, preventive and curative health care of good quality’) has been reduced to the commission’s work on mental health and its Beating Cancer Plan—both of which will fail without sufficient healthcare professionals.

To that end the EPSU has proposed recommendations on what such an EU action plan should include.