Housing is a huge source of carbon emissions. But decarbonising it effectively requires a sufficiency lens.

Residential housing accounts for about 19 per cent of greenhouse-gas emissions in the European Union and the United Kingdom. Both are committed to a rapid reduction in direct and indirect emissions from housing: the EU to a 90 per cent reduction from 1990 levels by 2040, the UK to 78 per cent by 2035. So the decarbonisation of housing is a major policy priority.

To achieve this requires raising the carbon efficiency of existing housing and ensuring that newbuild housing attains the highest, near Passivhaus, standards. The former is more important by far: some 90 per cent of UK emissions arise from the heating and electricity consumption of the existing stock.

At the same time, decent housing meets a basic human need and it is increasingly recognised that climate mitigation must embody social as well as ecological goals. This is all the more important once it is recognised that supply-side efficiency measures alone cannot achieve such a drastic reduction. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change acknowledges that demand-side measures are essential too. There is no hope of reaching ‘net zero’ by 2050 without changing everyday lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production.

But putting demand-sIde policies on the table begs the question of whose consumption should be reduced or recomposed. There is a strong normative case that necessities trump luxuries. Once that is accepted, maximum as well as minimum limits must be considered—across domains of wellbeing, wealth and income, consumption and production. The concept of sufficiency defines the space between a ‘floor’, to ensure a decent minimum standard for all, and a ‘ceiling’ above which lies unsustainable excess (Figure 1).

Figure 1: the space of sufficiency, between floors and ceilings

| Wellbeing | Wealth/income | Consumption | |

| Above ceiling | Excess | Riches | Luxuries |

| Ceiling | |||

| Sufficiency | Flourishing | Moderate incomes | Comfort goods |

| Needs met | Decent minimum | Necessities | |

| Floor | |||

| Below floor | Deprivation | Poverty | Lack of necessities |

Housing standards

We use this framework, as an appropriate moral and practical approach in our recent paper on fair decarbonisation of housing in the UK. We start by identifying (metaphorical) housing floors and ceilings. Ideally, this would entail deliberative mechanisms, drawing on lay as well as expert knowledge, as practised in some climate assemblies. But since these have not yet been used to determine UK housing standards, we define minimum thresholds for housing space using government measures—the ‘bedroom’ and ‘newbuild floorspace’ standards.

To define maximum thresholds beyond which bedrooms and floorspace can be regarded as ‘excessive’ is novel and more difficult. We draw on an exploratory study of a ‘riches line’ in London, which includes housing, and end up with two excess-housing thresholds: two or more bedrooms above the bedroom standard and more than double the floorspace standard.

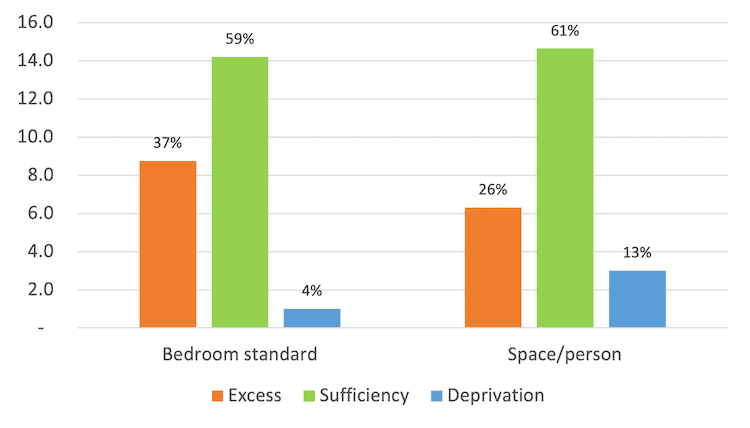

Between these floors and ceilings lies the sufficiency space. It is not limited to bare-minimum standards but includes ‘comfort’ housing right up to the ceiling of excess. Applying these thresholds to England, large numbers of households have excess bedrooms and space, outweighing the numbers in overcrowded accommodation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: proportions of households in England exceeding, meeting or falling below bedroom and space standards

Ninety per cent of excess bedrooms and 90 per cent of excess space are in the owner-occupied sector, the majority among older people owning their house outright. Though one million social-renting households suffer significant space deprivation, in this tenure group there is rough allocation according to need.

Environmental cost

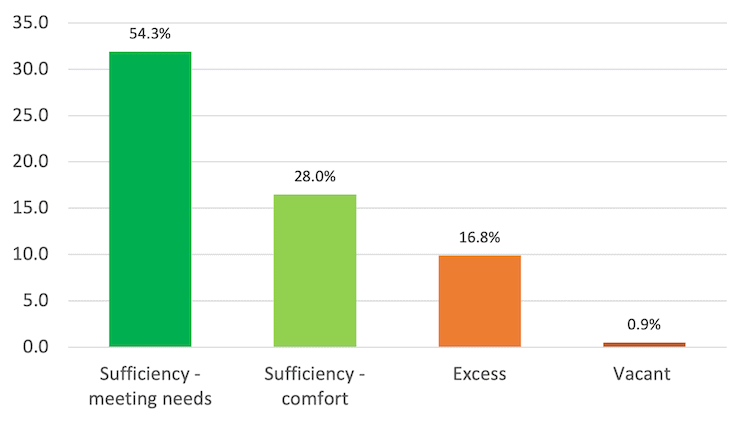

Excess housing also carries a heavy environmental cost, illustrated in the shares of carbon-dioxide emissions (Figure 3). One seventh of total operational housing emissions—9.9 million tonnes of CO2 annually—come from excess housing space. Indeed, the intensity (per square metre of floor space) of these excess emissions is 25 per cent higher than the average. Almost all (94 per cent) of these excess emissions come from owner-occupied housing; they are absent in social housing.

Figure 3: shares of CO2 emissions among household groups

Our findings reinforce the picture of a housing system with deeply embedded and unsustainable structural inequalities. Yet the dominant, cross-party consensus in the UK favours a ‘market-fixing’ approach—removing planning obstacles to build 300,000 new homes a year and adjusting allowances and benefits to aid purchase and renting.

The UK’s record on improving domestic energy efficiency is dire by EU standards: according to its Climate Change Committee, this is ‘the biggest gap in current government energy policy’. The Labour Party did promise a £6 billion fund to retrofit the housing stock but that appears to have been jettisoned. To be effective, it would in any case require building an entire provisioning system encompassing skills training, bulk purchase, new industries, standards, regulation and an overall planning agency.

Sufficiency strategy

A renewed carbon-efficiency strategy is clearly urgent. But a sufficiency strategy goes beyond this. Decarbonisation alone does not answer the question: what will the fully decarbonised housing stock be used for? Building new homes for the well-housed will not help deprived households and will incur further emissions. It will only add to calls for still more housing in the hope that space will trickle down to those who need it. The record of the past century provides no evidence this will happen.

A sufficiency strategy thus requires a suite of distinct policy programmes. First, alongside the escalating calls for radical reform of housing taxation and pricing, we should discriminate between sufficient and excess housing and target the latter. Examples include Germany’s Zweitwohnungssteuer (second-home tax) and devolved Wales’ surcharge on council tax (Britain’s local property tax) for empty homes. Implementing rising block energy tariffs—whereby an initial, need-based tranche of gas or electricity is free or low-cost, mounting thereafter—would be another application of an eco-social approach. To prevent affluent households simply paying the tax, direct licencing or regulation would also be needed, as in Barcelona.

Secondly, policies are required that achieve a better match between households and housing. Elderly owner occupiers inhabit the majority of excess space and a significant minority would like to downsize to a smaller dwelling. To enable this a joined-up suite of local interventions are needed, embracing information, incentives and where necessary alternative housing (as with the OptiWohn project in four German cities). At the other end of the age scale, the continuous rise in single-person households across the global north could be addressed. Experiments in co-living, house-sharing and other collective forms of householding in the UK and Europe can be fostered.

Thirdly, our evidence clearly demonstrates that social housing allocates floor space according to need rather than market demand. There is a strong case that any new build should be for social renting, not buying. In Britain, the ‘right to buy’ social housing established when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister undermines this goal and should be phased out. In addition, local authorities and housing associations could have rights of first refusal to purchase, repurpose and upgrade empty rental property.

Gaining support

These are radical proposals but, without them, however carbon-efficient the housing stock is made, it will not become more effective at delivering decent accommodation to households who need it. It will also continuously encourage new housebuilding with associated environmental costs.

A sufficiency strategy would demarcate a ‘housing corridor’ for the UK, moving from where it is now to a fair, decarbonised future. It would form a significant element in an eco-social policy for universal basic services in Europe as a whole.

There is evidence that such sufficiency policies are gaining support. A recent survey of recommendations from citizens’ assemblies across the EU found a greater willingness to countenance sufficiency policies than among European governments, influenced by short-termism and interest-group lobbying.