Covid-19 has had a major impact on workplaces but unions have struggled with health-and-safety responses.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020, workplace transmission of the coronavirus has been at the centre of attention. Given the traditional commitment of trade unions to occupational health-and-safety standards, unions might have been expected to be strongly involved in containing the pandemic.

Our recent comparative research—taking in Germany, Luxembourg and France—however shows that unions have experienced increasing difficulty in doing so over the course of the pandemic. The challenge has been to develop policy positions on occupational safety and health (OSH) that simultaneously address the variegated situations and needs of members and balance their representation with public-health considerations.

Particularly contentious

At the time of the first lockdowns in 2020, union positions were relatively clear: while employers mostly called for business continuity, unions emphasised the precautionary principle and urged suspension of business activities. Governments tried to find a compromise.

With the initial reopenings, the situation became more complex, due to the heterogeneity of interests within the labour force—varying as these did with workers’ degree of health vulnerability, age, economic situation, the nature of their work and their degree of isolation. Two issues proved particularly contentious: workplace test strategies and mandatory vaccinations.

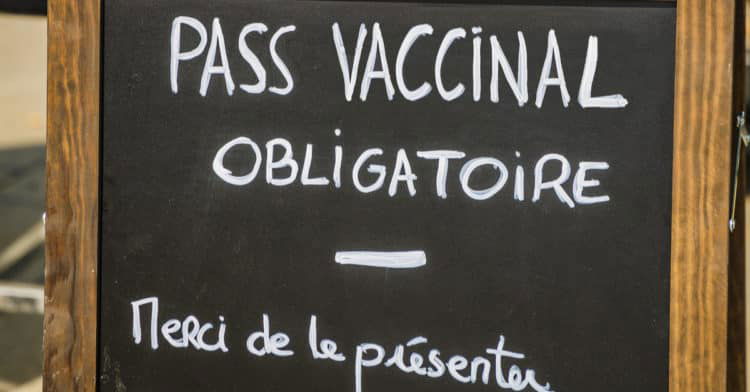

Union positions on workplace tests themselves diverged. Many French unions opposed mandatory testing and the introduction of the health pass, sometimes even taking to the streets. In contrast, unions in Germany and Luxembourg agreed, if sometimes half-heartedly, to the introduction of the ‘3G’ rule—geimpft, genesen, getestet—and associated pass, allowing only vaccinated, recovered or negatively tested workers in workplaces.

Unions’ reticence towards mandatory testing for unvaccinated workers may be explained by the fact that such policies transferred responsibility for monitoring and sanctioning recalcitrant employees to employers. This rendered employers the only legitimate actor on workplace health and safety, instead of engaging workers’ representatives or imposing policies in the name of public health.

Mandatory vaccination

Mandatory vaccination came to the fore because of insufficient vaccination in the three countries we investigated. France and Germany therefore required that health workers be vaccinated, which in Luxembourg is under discussion. Though from a public-health standpoint vaccination reduces contagion and protects against severe illness, unions have tended to oppose mandatory vaccination in general.

According to our research, unions’ reluctance to take an active pro-vaccination position mainly stems from the pressure of unvaccinated members and fear of membership losses. It may, however, also be due to the fact that unions, having frequently seen their representativeness questioned by governments and employers, tend to conceive their representational function in terms of a simple reflection of member attitudes, rather than a political mandate built through dialogic democracy.

Union scepticism towards mandatory workplace tests and vaccinations however risks jeopardising a key principle of OSH—the legal obligation of employers to protect workers once the necessary means to do so are available. Indeed, if individual workers are treated as free to choose to remain unprotected against hazards or even consciously to expose themselves to them, the employer obligation regarding OSH is in danger of being nullified.

Risk assessments

The pandemic has challenged unions in many ways and so far they have not been able to take advantage of it to push through stronger OSH policies. Unions have rather stressed the usefulness and importance of existing European and national regulations on risk assessments.

These have to be carried out in workplaces to minimise potential risks to workers’ physical and mental health. Already before the pandemic, however, the most recent ESENER survey by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work had underlined the unequal implementation of risk assessments among European Union member states, sectors and companies of varying sizes. The pandemic has underlined that the hazards involved in many jobs and tasks have never been properly assessed.

Workplace representatives—often unionised in the three investigated countries—play an important role in the implementation of OSH in workplaces, in monitoring risk assessments and checking whether they are really carried out. Yet certain institutional developments have challenged them in exercising their role.

In France, the abolition in 2017 of health, safety and working-conditions committees reduced the influence of workplace representatives, further undermining a workplace ‘culture of prevention’. In Germany, the number of works councils and employees represented by them has shrunk in recent years. Consequently, workplace monitoring and enforcement of risk assessments have become even more patchy.

Key tool

Against this background, unions should consider reprioritising OSH. Risk assessments are a key tool, insofar as they are carried out regularly and cover a range of potential physical and mental hazards. As the necessary legislation exists, unions could be(come) key actors in implementing the related rules in practice, but they need to make this a strategic priority in the years to come. If successful, unions and workers alike could benefit.

This could be a timely choice, given another major development changing the world of work and heightening the importance of OSH—climate change. Extended heatwaves and heat stress, plus extreme weather episodes, will confront many industries with unprecedented difficulties and losses of working hours. In the decades to come, these will require sustained and coherent strategies for risk anticipation and mitigation, if healthy and safe working conditions are to be guaranteed.