The big American digital platforms—Meta (Facebook), Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google) and Apple—have accumulated a mass of economic power unprecedented in the history of capitalism. Their Chinese counterparts (Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent) are doing likewise. With its ubiquity, across sectors and geographically (albeit excluding China), physical as well as digital, Amazon is however paradigmatic.

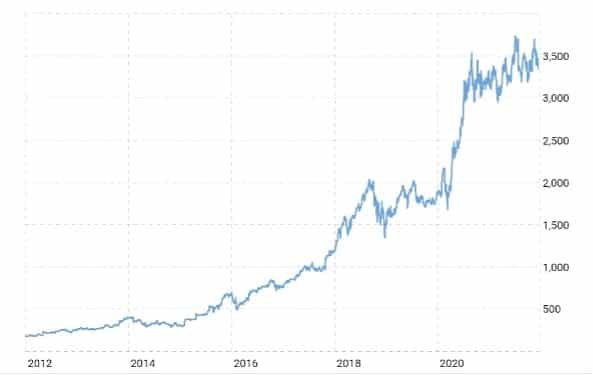

Such power can be viewed from different angles. First, there is market capitalisation: with a vertiginous growth in its share price (Figure 1), Amazon’s value of $1.68 trillion is greater than the gross domestic product of Spain and about to overtake that of Italy.

Figure 1: evolution of Amazon stock quotes, 2012-20 ($)

Then there is the wealth accumulated by those at the top: with a net worth of $197 billion, Jeff Bezos (founder and former chief executive officer) is third in the global billionaire ranking compiled by the business magazine Forbes, where he is accompanied by eight other founders, CEOs and top managers of Microsoft, Alphabet and Meta.

Another benchmark would be the continual, though often unsuccessful, attempts by governments and anti-trust authorities to contain this power by punishing anti-competitive practices or increasing the tax demanded of Amazon and other platforms. Yet another measure would be the plethora of political and trade union conflicts which have seen the platforms accused of exploitation of workers, discrimination and anti-union policies (Amazon and Alphabet), distortion of public debate and electoral processes (Facebook and Twitter) and negative environmental impacts from their digital activities.

Fundamental engine

The concentration of power in large innovative companies has been characteristic of capitalism since its origins. Karl Marx, Joseph Schumpeter, Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin recognised that large technological oligopolies and transnational cartels constituted a fundamental engine of economic, social and technological transformation—as well as a primary cause of class polarisation, political instability and war.

Today’s platforms are however able to control and condition the actions of workers, consumers, suppliers, competitors and governments much more intensely than the large multinationals of the last century. To grasp these discontinuities, it is necessary to go beyond a view of economic power confined to the market.

There are very useful insights in explaining the platforms’ concentration by ‘demand-side externalities’: the utility users derive and thus their willingness to pay increases as their number increases. The same is true of ‘multi-sided-network effects’: the utility derived by agents on one side of the market, such as Amazon consumers, grows as the number on the other side, such as companies using Amazon to market their products, grows. Yet these mechanisms characterise many other sectors too—computer hardware, software, credit cards—and thus are not sufficient to explain the power large platforms enjoy.

Monopoly capital

We have attempted to do so by referring to a particular strand of literature—the theory of ‘monopoly capital’ developed by Paul Baran, Paul Sweezy and Keith Cowling, among others. The latter focuses not on market relations as conceived by standard microeconomic theory but on the ability of the firm to control the economic space and to exert influence and hierarchical power outside its formal perimeter—physical, legal and market-related. Jan Eeckhout calls it the ‘moat’ they construct.

Our analysis centres on Amazon and identifies four factors in the power of platforms:

- growth and sectoral diversification,

- research and development and a monopoly of key technologies,

- fragmentation of labour and its control and

- the conditioning of governments and retaliatory power.

What coheres these factors is the ability to control all the information produced within the platform’s sphere of influence—internet segments and their physical counterparts—effectively subordinating the actions of other actors to the strategies of the platform itself.

This is somewhat similar to what Shoshana Zuboff calls ‘surveillance capitalism’. In this context, however, the capillary control of (digital) information is not placed at the centre of the scene as an instrument of ‘commodification of privacy’. Rather, such control greatly increases the platform’s ability to influence the agents with whom it interacts and so to extract value—thereby allowing it to expand its sphere of influence at significantly lower cost and a much faster pace than the multinational corporations studied by Baran and Sweezy and their successors.

Firm control

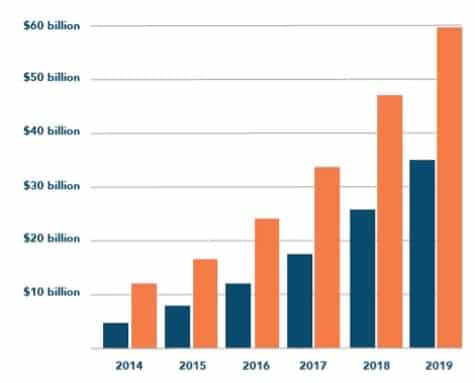

In the Amazon case, exponential growth and diversification come from its control of the strategic services—cloud, logistics, advertising and online profiling—instrumental to producing, distributing and selling any other good (Figure 2). More, it systematically resorts to imitation and predatory pricing to colonise the product segments with greatest growth prospects.

Figure 2: Amazon revenues from tariffs paid by third parties (orange) and network services (blue)

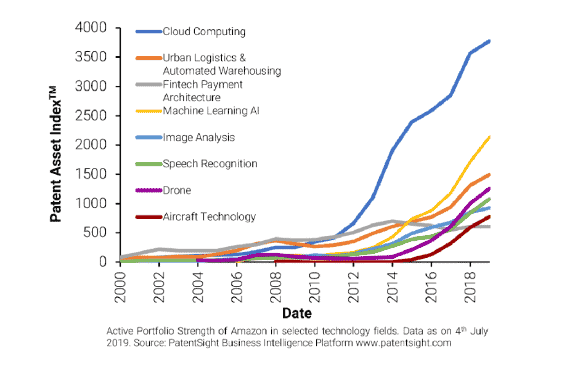

Amazon competes with other major platforms in its attempt to monopolise technologies such as ‘big data’, cloud computing, artificial intelligence and machine learning. These are essential to maintain firm control of the network (digital and physical) and, above all, the information within it. The tools used to ensure dominance are skills attracted from major universities, R&D, patents (Figure 3) and acquisition of innovative start-ups.

Figure 3: Amazon patents by technological domain

Furthermore, the power of Amazon is linked to the control and exploitation of a huge and heterogeneous mass of workers. This includes those operating the physical component of the network—the logistics workforce subject to high exploitation via outsourcing and use of the most advanced monitoring and efficiency-enhancing AI technologies. But it also includes the digital workers—the myriad individuals scattered around the world, paid very little to carry out the tasks necessary to ensure the functioning of the network and the algorithms on which it rests.

Finally, Amazon’s power reflects the platform’s ability to influence governments and public authorities by resisting hostile regulation in the areas of taxation, competition, privacy and trade union rights. This is closely linked to control of a politically vital commodity—information—as well as seduction of a complicit consumer base, now almost coinciding with the entire western population, which would hardly vote for a party with an agenda hostile to Amazon services. Together with its employment relevance in the physical world, which makes it different from other big platforms, this gives Amazon far greater retaliatory power against governments than pre-internet multinationals enjoyed.

Progressive strategy

The power Amazon has today is the result of an act of original accumulation exercised on an uncontaminated space—the ‘commercialisation of the internet‘, enabled by political choices by United States governments in the early 1990s, from which today’s platforms originate. Yet their power can be challenged, provided one is willing to go beyond conventional anti-trust policies and privacy protection. These do not call into question the privatisation of digital information—which could even be exacerbated by stronger privacy-protection rules—still less its profit-oriented use.

A progressive strategy, aiming for economic and political democracy, should strive towards the decommodification of personal data through socialisation of data and platform infrastructures. The challenge will be to democratically manage data for society as a whole without foregoing the opportunities platforms can provide for shared prosperity.

In this perspective, Amazon’s capability to co-ordinate the actors in its network and efficiently to plan the production and distribution of goods and services—thanks to the harnessing of a growing pool of data—provides us with a glimpse of the shared social benefits which could derive from a radical reorientation of its infrastructure towards the public good.

An earlier version of this article was published in Italian on Il Menabò di Etica ed Economia